BIO AND STATEMENT

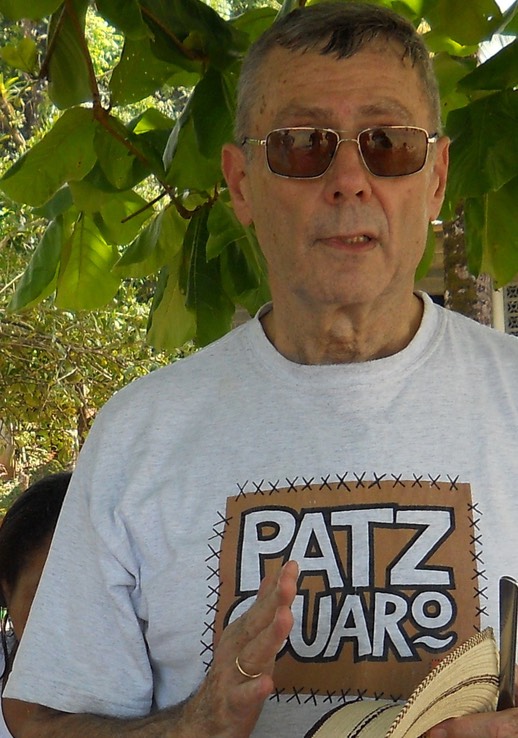

Born in Princeton, Indiana, E. K. Newton, III has done creative writing since grade school--one novel, thirty short stories, and fifty-three poems. Lived two, formative, pre-teen years in Panama. Earned an AB degree in Political Science at Brown University. A Peace Corps Volunteer in Panama for three years. Trainer of Peace Corps Volunteers in Puerto Rico for thirty months. MAT in Spanish at Indiana University. Taught Spanish for 36 years at the high school level. English teacher for adult immigrants 1985-2014. His wife is Panamanian, and his two daughters are bi-lingual, panagringas. He and his wife reside in Ocala, Florida.

____________________________________

Con este cuento corto, “My Mother’s Daughter,” le rindo homenaje al gran poeta e intelectual mejicano Octavio Paz, porque su obra maestra, “El Laberinto de la Soledad” nos proporciona una extraordinaria ventana a la complicada escencia del alma del mejicano. Paz nos revela las fuerzas históricas y las interacciones de las diversas culturas de las cuales han provenido no solo el mejicano sino su contexto, o sea la sociedad mejicana y el ámbito que ocupa hoy en día. Para mí la gran meta de las bellas artes es la de ofrecerle al ser humano la oportuunidad de examinarse, y así conocerse mejor—tanto sus rasgos idiocincráticos como lo que tiene en común con los demás—tanto sus grandes hazañas como sus torpes fallas—tanto sus maravillosos sueños como sus más horrendas pesadillas—todo esto, para así poder mejorar la condición de la raza humana.

My Mother's Daughter

“A cada minuto hay que rehacer, recrear, modificar el personaje que fingimos, hasta que llega el momento en que realidad y apariencia, mentira y verdad, se confunden.”

“At every moment one has to remake, recreate, modify the character one pretends to be until the moment arrives in which reality and appearance, the lie and the truth are

confused.”

Octavio

Paz

The Labyrinth of Solitude,

Part II: Máscaras Mexicanas

It is early evening. I have come to keep my mamá company. She has been sick with bronchitis for several days now. We are talking about my father’s trip to the state capital. He has gone there to join the demonstration to demand that the governor free Joaquín Moreno. It is past twilight, and my father is overdue. Clearly, my mother is very uneasy, but she says, “What can I do, mi hija, you know politics is your father’s life blood. You see how he becomes when he is involved with it. And he helped to plan this demonstration.”

“I know, mami, I know.” I agree. I have seen the charge of energy surge through my papá when he grabs the microphone at the registration rallies, and my brother Lazarito and I have been brought up on the stories of how our parents met on the barricades back in ‘68. They have told us the stories of how many of their student comrades died just blocks from the Olympics while the world press focused only on the gringos’ black runners, raising their fists in the air to protest their own country’s racist policies.

“Your father could be a great lawyer, you know,” my mother continues, “He’s a natural. When he received his degree, I hoped it would mean that he would settle into the profession—I hoped that the law would replace the politics, but it has not been that way, and I am afraid for him tonight.”

“Afraid?”

“Yes, mi hija, the governor is crazy with ambition, he wants to be president. There is no telling just what he will do: he will let nothing get in his way. Your father and the governor are long-time enemies—you know this, I know you have heard your father ranting about the man’s corruption—and this protest is a big embarrassment for the governor—there will even be members of the foreign press to cover it. So I must worry until your papi is safely home tonight.”

The concern has stamped itself on mamá’s face, etching deeply-creased lines that relax only momentarily as she retreats behind her handkerchief in a spasm of dry coughing. She has been sick for three days now. There is a red puffiness around her eyes from the constant coughing. That and the worry make her seem much older.

“You know, mami,” I say in hopes of distracting her a bit, “I heard Mr. Ramírez talking at the banquet last Saturday. Papi is a lot like him.”

“Which Ramírez? You mean my comadre Rosaura’s husband, Beto?” Mamá’s gentle eyes seem to harden momentarily.

“Yes. They gave me your seat, it was right next to him,” I continue, “He went on and on, all during dinner, nothing but politics. He and papá seem to suffer the same addiction. You and your comadre have so much in common, working together, and both married to political addicts. One minute Rosaura, ...I mean, your comadre Rosaura, one minute she was telling me how happy she is that her husband is finally out of politics, the next thing I know, when she left the table to greet some friends, Mr. Ramírez spent nearly the entire time she was gone telling everybody at the table about how he wants back into politics—that he will be running for Municipal President again in the next campaign.”

As I speak, I see that a smile, which I recognize to be ironic, slips across my mother’s face, then vanishes. She says only, “You will do well to maintain the titles of respect for your conversations in public, my child.”

I nod, accepting her mild reproach, and continue, “It must have been twenty minutes, the whole time Beto —I mean, Mr. Ramírez—was talking about PRI politics, about how much he misses it, about his civic duty—about needing to do more for the country...”

“No te creas, my child,” mamá says simply, “You should know, things in this country are never as they appear. You must not believe him.” Sadness has crept into her voice as she continues, “I suppose it is time for you to understand some things, my child. My comadre Rosaura is your brother’s godmother because she and I work together, and when we first arrived here, I was already pregnant with Lazarito. I didn’t know anyone. She seemed warm, and I must admit, she extended a hand of friendship to me. But things changed. If you think her husband is ambitious about politics, I must tell you that my comadre Rosaura has enough ambition for the both of them. It has been very difficult for her to accept her husband’s failures. She dissembles well, but it has been hard for her over the years—your papá’s success, rising to Diputado while her Beto failed to ascend beyond the presidency of the municipality, even with his family’s name and all of PRI’s power backing him. Your father’s success has been like salt in an open wound for my comadre.”

“But why, are you not friends and colleagues in the school?” I ask: I am surprised, and a bit confused.

Mamá leans forward, her voice becomes deeper—flatter—more charged with emotion. There is a pain in her eyes that I do not recognize, “My child, you need to know this. Rosaura and her husband consider us to be nacos. For them and those of their social circle, we are unclean and uncultured, just because of our peasant roots—Beto Ramírez’s family has always been well seen, his is one of the families here. Ramírez is an old and respected sir-name—Beto and your father have been the fiercest of political enemies from the beginning. When Beto occupied the Municipal Presidency last time, things were very bad. PRI has always done as it pleases, it has had absolute power for decades, ever since The Revolution. But Beto’s abuse of his authority was terrible, almost unprecedented, even by PRI’s standards. Ask anyone...”

“She thinks of us as nacos?” I ask aloud, but more to myself, thinking of the implications.

“Yes, mi hija, nacos,” my mother hardly pauses. From somewhere deep inside, once having broken the surface, mami’s long held-back words tumble over one another. I can only nod and listen, “There was so much corruption in Beto‘s administration, junkets to Cancún, to Acapulco, even to Paris. You name it—the whole family at the expense of the municipal government—they had three guards around my comadre’s house day and night, and—you saw it, Emiliana—but you may not remember, or maybe you were too young to understand, they had two separate, stretch-limousines, the chauffeur and assistant of each, armed to the teeth, one bringing my comadre Rosaura and the other bringing her kids to school. People said both cars were bulletproof, I don’t know—cars all look the same to me. And at the very same time, Beto was maligning the public school teachers, calling them beggars and good-for-nothings, simply because they were asking for increased support from his municipal government—not for better salaries for themselves mind you—they just wanted enough funds to be able to buy classroom supplies for their students.”

The torrents of mami’s words obey only their own imperative. I listen in shock.

“Things got very heated, there were demonstrations, boycotts, even a general strike. I was almost certain there would be real trouble. Remember, I sent you and your brother on a vacation to stay with your grandmother in Zacatecas. It was during this time that your father was thrown in jail. He and Pietro Mancini—you know, Magda’s husband—and two others, the four of them had led a demonstration—a simple, peaceful act of civil disobedience—they had men and tractors blocking the entrance and exit ramps to the major highway from every farmland road between here and the state capital—the government was not honoring its commitment to the sorghum farmers—eventually the government gave in, but not before your father and the other three were detained and then taken to the municipal building….”

My mother’s voice quavers—she must see the shock of her words register in my expression, my papi in jail! Her own eyes are wide with fear, I assume, as she relives the events.

“...Luckily, someone called here with the news that the four of them had been taken prisoner. There was no time to lose. We all began to contact everybody we knew, relatives, the neighbors, and the neighbors got hold of their friends—I got in touch with Magda and the wives of the others—in ten minutes we were on our way—people from all over town—we converged on the municipal building—everyone knew what was at stake –we camped outside, day and night. No one slept. There were hundreds of us, people were bringing us food and water, others brought us petates to nap on. We kept the vigil, Emiliana, because we were almost certain that the plan was to disappear them. It had happened here before...We didn’t know exactly what part of the building they were being held in—and this is the sad and terrible part, Emiliana, each day my comadre Rosaura’s Beto would come and go, and each time I shouted to him, ‘For the love of God, Beto, where is Lázaro? Is he in there –where is he?’—but do you think he would answer me?—No! That coward! He just looked straight ahead, like I wasn’t there. Can you believe it, my child, even though his wife is your brother’s godmother? It didn’t matter to him. Beto pretended I wasn’t there, standing, maybe three feet away, crying and begging him. If they had disappeared your father and the others, Beto Ramírez clearly would have let it happen. In fact, he may actually have been in charge of the whole plan.”

I feel mamá’s eyes fix on me momentarily. I look away, not wanting her to see my tears. She senses my rising anger, my feelings of betrayal.

“Emiliana, I have wanted to tell you, my child, but you were too young for these things,” she takes my hand and gently squeezes it, then continues, “Finally, after three days your father and the others began to yell from inside so that we would know where they were, and that they were still alive. The four of them were being held in a single tiny cell, six-feet by six-feet—three days—they had to take turns sleeping. They could hear us outside but were afraid to make noise, afraid of reprisals, until, after three days, they were more afraid we might leave—and without us, they knew what would happen to … but we would not have left because we, as well, knew all too well what would happen.”

Her voice, rasping now, forces mamá to pause for a sip of water from the glass on the nightstand next to her. She dabs at her eyes with a tissue then continues.

“So when we finally heard them, after all that time of not knowing if they were alive or dead, I was so relieved at first, and then I became so angry that I drove home and called the Governor himself. God only knows why he chose to answer—I was so mad and afraid that I screamed at him that he was a coward and that they had violated Lázaro’s congressional immunity rights. Then I called the adjutant general, an old classmate of your father’s. A few hours later, they released your father, and after that the others, one-by-one. But there is no doubt in my mind that they would have disappeared them—and all the time, Beto going in and out of that building, knowing that your father was there, yet telling me nothing, not even acknowledging…”

Mamá tries to choke back her sobs, but her small frame shakes violently as her sobs turn into coughing spasms. There follows a moment of silence as she gathers herself then says quietly, “Forgive me, my child, it’s just that I have carried this for such a long time. Your father and I embraced when he was released, and in that embrace was an unspoken agreement never to discuss what had transpired. I have never told the story to anyone…one never knows who to trust, things here are never as they appear…but perhaps now you will understand better why I’m concerned that your father has not returned yet. But now that you know our secret, Emiliana, you must carry it with you. Do not talk about it with anyone, not even your brother. It is our burden, yours and mine. See, I already feel better, you have lightened my load—at the same time I am pained to have given such a heavy thing to you, my child, but you are becoming a woman, Emiliana—look, already you took my place beside your father at the banquet…little did you imagine the price of the ticket. Thank you for helping me to pass the time—I know that you have homework to do, and I must rest if I am to go back to work tomorrow.”

“Will you be okay, mamí? My homework can wait,” I say apologetically, but I really want to ask, How do you and Rosaura share space and time together? How do you work together day after day? How can you control the anger? and Why don’t you just call papi, he has his cell phone…but I remember that for mamá’s generation, like all those that came before, these things are different, that often, the man’s and the woman’s worlds must not intersect. If she calls when he is in the company of others, papá will resent the implication of her call. His companions will joke that he is a mandilón, that he must do his wife’s bidding even when he is beyond the walls of our home.

Besides, in my parents' world, children are to be seen, not heard. So instead of saying anything, I turn toward the doorway, vowing to myself that things will be different with my generation. In a strange way I am relieved that I do not have to share the intense feelings and turmoil my mother’s story has unleashed in me. I take my leave with a platitude, “I will keep an eye out for papá,” I say. Then I lie, as social convention requires, “I’m sure he will be home before we know it, mamá. The meeting probably began late and, you know papi. Undoubtedly he has stopped somewhere on the way home for tacos and conversation with some of the others.”

“Sí, mi preciosa, without doubt,” a thin smile forces itself onto mamá’s lips, but vanishes quickly.

I pause in the doorway and tell her that I love her, and that I am happy to share her burden, and that she needs to sleep, and that I will come to keep her company later if my homework doesn’t take too long.

But the homework does take too long, because I can’t concentrate. Nacos! I spend a lot of time with the Ramírez kids, and that’s what they think of me, for them I am unwashed! Uncultured! Just wait ‘til I see them! Nacos! Emiliana, now get hold of yourself—you promised mami. Why can't she just call papi? Why must we women suffer in silence? After several attempts to bring my mind to my homework fail, I give up on it. But I decide that mamá must be sleeping, that it’s too late to go back for another visit, and anyway, I need time to process it all. I decide to do my nails since it has been almost two weeks, and it is the sort of mindless task that takes total concentration.

At about ten o’clock, Lazarito and some of his friends shout up to me from the wrought iron gate outside. They tell me they are going out for tacos if I want to come. I decline the offer. When I look out the window, I see that my father’s car still hasn’t arrived.

Mamás words and images of Rosaura’s kids, Junior and Rosanna, laughing at me play themselves over and over in my mind. They consider us nacos! And just who gave them the right… I brush my teeth, change into my pajamas, and sit down at the vanity to brush out my hair, yanking the long strands into submission. I tell myself, Things will change, my generation will be different. Finally, I drop into bed. Surprisingly, I fall asleep quickly. But it is an uneasy sleep.

Just after midnight, I awaken to go to the bathroom. I look out the window. The Chevrolet Cavalier is still not in its customary place. Poor mamá, I hope she has taken a heavy dose of cough medicine. Then, I realize that since I didn’t join Lazarito for tacos, I am actually quite hungry. I go downstairs for a piece of bread from the pantry. I bring it back up to my room and turn on the television, just in time to catch the end of a gruesome film about a writer and a mass murderer. When the station signs off the air, I turn off the set and the bedroom lights. One last look out the window, still no Cavalier. I drop into bed again. Sometime before dawn I toss myself into another fitful sleep.

Street noises startle me awake. It is well after sunrise. The light from the window is intense. Eyes only half open, I grope my way to the window. Half afraid to look because of what I may not see, I force my eyes to focus in the searing light. My chest heaves involuntarily as I release the spent air of my held breath. Under the bright, cloudless morning sky, just inside the gate of the small courtyard, my father’s car gleams white in the sunlight. Relieved, I shower, comb the tangles from my hair and dress quickly, but leave my makeup for later. No doubt papá will have an interesting anecdote or two to share over breakfast—some injustice righted, his most recent, tiny victory against PRI’s monolithic political machine…

“Buenos días, Emiliana,” mamá greets me as I come into the dining room. “I trust you slept well, my daughter. Your father is still sleeping. He got home very late. He told me he hopes that you will forgive him for missing breakfast. He promised that you and he will talk later. I told him that your first class is in the afternoon today. I promised him that you would at least sit with him for a late breakfast. He says to wake him by ten o’clock if he is not already up.”

Mamá is dressed for work. As I move to my usual seat, she places a basket of freshly heated tortillas on the table, we embrace then both sit down to breakfast. As we exchange pleasantries across the table, I take note that last night’s heavy creases of worry seem to have vanished, they have been disappeared, behind carefully applied doses of foundation powders, eye-shadow and lip gloss. Under the gracefully elongated arcs of her carefully plucked eyebrows, mamá's eyelids are shadowed in green, punctuated by thick black, meticulously curled, eyelashes that accentuate the almond shape of her clear, soft, dark brown eyes. There is no hint of the redness or the puffiness from her coughing and crying. Gone is her chest congestion. There is nothing, not the slightest trace of last night’s extreme pain, its desperate agitation or her seemingly overwhelming angst. In the unforgiving morning light, my mother is ready for another day and for the hundred mundane interactions it will bring with her comadre Rosaura and the other women of Rosaura’s ilk. Mamá is the perfect image of dignity, serenity, control and self-confidence. I look at her and suddenly I understand. I promise myself that when the afternoon comes, in spite of my anger, my pain, and my desire for revenge, I shall be ready too. After all, I am her daughter, and I must be worthy of her, and of the secrets, and of the world we share.