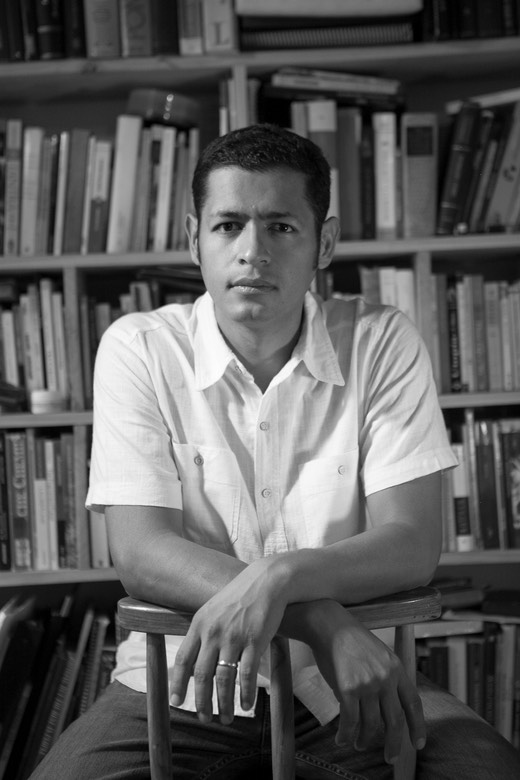

BIO

Javier Kafie (Mexico City, 1982) grew up between Mexico, Central America and the United States, finishing a degree in Literary, Cultural and Media Studies at the University of Siegen, Germany. From 2004 to 2007 he works as an editor for the student magazines Fool on the Hill and Polyphony Online. In 2009 he moves back to Central America, directing in 2011 the short documentary Perkin. In 2014 he produced the documentary El Salvador: Four Cardinal Points and the fictional short film Perfect Together. In 2015 he wrote and produced Nothing, winner of the Short Fiction category in the ICARO Central American Film Festival. He lives in San Salvador and works as a writer and filmmaker.

Dust

Rosario turns on the gas burner and puts away the matches in her apron’s pocket. The kitchen clock marks 20 minutes to midday, and a few meters away Selma is sweeping the dining room. Rosario looks at Selma and smiles. Farther away there’s the sumptuous marble terrace where the gardener is trimming off the sprouts of the rose bushes before the incandescent sight of San Salvador at noon.

Rosario takes the lid off the pot. The beans are already boiling, and she calculates that they’ll be ready in about fifteen minutes. She takes out a hotplate from the cupboard, puts it on the flame she just turned on, takes a little bit of corn dough between her hands, makes a little ball, and starts to shape it in the form of a tortilla.

Then, the whole world leaps.

Rosario looks with sudden dread on the direction of Selma, who returns her an equal glance. The world shakes again with rage and Rosario can barely keep on her feet. She manages to turn off the gas knob, but the pot with the beans jumped so hard that the boiling liquid burned her arm and elbow. Silence. Then the earth jumps again, and again, and now it doesn’t stop. And somehow Rosario is now sitting on the floor right next to the beans pot, the hotplate, the sugar and flour jars, the frying pans, the coffee can, the cups, the soup bowls, the pitchers for lemonade and the silver cutlery that the bosses brought from Europe on their last trip. Rosario doesn’t feel the burns from the beans broth on her arms, elbows and buttocks yet, but she will feel the sharp pain hours later, under absolute darkness.

–Stay there! –She screams to Selma, and starts crawling towards her–. Stay there! –and she sees Selma bouncing on the floor, crying, still holding the broom on her hands. Something heavy falls on her leg, but she keeps on crawling. And when she reaches Selma, she sees the whole world and everything with it coming down, and before there’s complete darkness Rosario sees a rock or a brick falling on Selma’s head, and then everything turns to black.

***

We live surrounded by noise. The voices of people talking, the noise of cars passing by, of the coffee machine, the ceiling fan, the TV turned on, and the endless small noises produced by the simple act of living. Only when you’re surrounded by absolute silence –when the high pitched whistle on the ears ceases– you realize how mighty, how overwhelming silence can be.

–Selma! –Says Rosario–. Are you alive, Selma…?

–Selma! You’re not dead, right, Selma? Tell me you’re not dead…

Besides silence there’s darkness. Strict darkness and dirt mush on the throat. Rosario moves her hand forward, among rocks and hard, unrecognizable objects, until she touches the soft surface of skin.

–Selma, you’re not dead, right? Please tell me that you’re alive.

Her hand moves over that skin, and she realizes that she’s touching a leg. Then she advances on a layer of something that feels soft. She recognizes the consistency of that layer, and recognizes it too in her throat. She coughs.

–Dust –says Rosario–. It’s dust.

She repeats it because she realizes that she’s alive by the simple articulation of a word. “We’re covered by dust”, she thinks. Then her hand recognizes the fabric of a dress, then an arm, and a hand. Her fingers and her hand and her body is in a very narrow space. However, Rosario manages to crawl closer to Selma’s body.

–You’re not dead, right, Selma?

Her hand reaches Selma’s neck, it feels warm and soft. She touches her face and her head, and recognizes a dampness on her hair. Rosario retreats her hand and puts her fingers in her mouth, and after surpassing the omnipresent taste of dust, she feels a metallic flavor.

–Blood –says Rosario–. No! –She yells.

She manages to drag herself next to Selma, and screams two or three times her name. Then she moves her lips close to hers and stays still, very still, until she feels a mild breath.

***

Although I can’t see her buried down there, wounded and wrapped in total darkness, I know that Selma always thought herself to be jinxed.

Since childhood she had the double misfortune of being too naïve and too pretty. A boyfriend took advantage of that innocence when she was fourteen years old, and a few weeks later she suffered her first abortion. Thus, at fifteen a rough callus started to grow around her heart, and after that she wasn’t able to fall in love. Actually, Selma probably never knew true love.

At sixteen she found her first job as a maid in San Salvador, and there she met Enoc. He worked as a gardener twice a month in the house where Selma cleaned, and from the first moment he saw her, he fell hopelessly in love with her round and childish face, the dimples of her smile, her abundant and black hair, the brownest eyes he had seen, and her small and slender body. But by then Selma had already learn to say no, and she repeated him that no so many times that even the whores from South Tenth Street couldn’t soothe Enoc’s wounded pride –nor the urgency to penetrate that small, olive-skinned body. So one day Enoc stood proudly in front of her and told her something that came up from the deepness of his heart:

–If you don’t belong to me, I swear that I’ll kill myself.

Selma didn’t know if he was telling the truth, nor did she know how to react. She couldn’t repress a nervous smile as she dodged him skillfully, reaching the exit gate of the residence just in time, for she had to buy bread for dinner. But two days later, Enoc ringed the bell of the residence, and as they opened he fell flat on his face, the stench of ant’s poison ascending from his gut. He told to whoever wanted to hear that he was dying of love for Selma.

***

It’s dark, and Rosario holds the warm body of Selma on her burned arms. Rosario is ten years older, and knows more than enough about the bad cards that this land delivers to people: she was still a child when an overflown river destroyed her house. Many years later, an earthquake took her dad away, for he went out to work one morning on a construction site in San Salvador, and his body was never found among the rubble.

But Selma is barely nineteen years old, and as she touches her, Rosario feels that this child doesn’t deserve to be buried under three floors of rock and concrete.

–I’ll die without confessing –says Selma, with a dry voice. It’s not even a complaint, but a resigned statement, another way of filling up the darkness.

–You’re not going to die –Responds Rosario, not so sure of her words. “You’ll see that they’ll pull us out,” she thinks, and tries to swallow dirt and saliva as she imagines herself alone in the dark, holding Selma’s dead body, waiting to die of thirst, hunger or lack of fresh air. She also swallows the fear of telling Selma that which she wanted to tell her for so long, and which she always believed that wouldn’t ever tell.

***

With Rosario, things were always painfully simple. She was ugly and from a poor and large family, and she was too young to realize what was happening when her mother handed her over to an old man in order to pay him an old debt.

Then, at fifteen, Rosario was suddenly the wife of don Chente, a small land-owner from a town in the proximities of the capital.

Don Chente was about sixty years old, and he’d die a few years later by falling from his horse, drunk. His first wife had died a decrepit death –a poorly treated sickness at the capital’s public hospital. And although by that time Rosario was only a child, don Chente, at his age, would not do without the help of a woman to look after him.

At the beginning, don Chente tried to be affectionate with Rosario. He might have treated her somewhat coldly and with rudeness at times, but he always respected her. We will never know if that respect was due to his age and experience, or because he was just afraid of losing her if she’d fall in love with a younger man.

Rosario’s first sexual experience was strange. Or at least, it wasn’t what she expected. It happened during the second or third night that they were living together as a husband and wife, sharing the same bed. Don Chente ventured the first caress, and Rosario thought that finally all those fantasies that had gone through her head while she’d masturbate behind closed doors in the latrine would come true. At last, a man would “break her insides”, as he mother had once explained her. But it wasn’t like that. Don Chente’s body came closer and closer to hers, and then she felt something like a hot and flabby banana scrubbing up against her belly. She felt Don Chente’s sour breath very close to her mouth as he told her “grab it”. Without quite knowing what to do, she held his penis real tight, and a few seconds later she felt a warm and viscous liquid filling up her hand and her belly while don Chente kept on rubbing frenetically against her. Then she felt don Chente’s body lose all its tension, and when she felt him sleeping with faltering breathing, Rosario brought her fingers closer to her nose in order to smell the liquid that had just come out of her husband. Then she heard a man’s voice tell her hoarsely: “Don’t be filthy. Go wash yourself!”

***

–I’m thirsty –says Selma once again.

Rosario stretches out her hand to a near-by surface –which until recently could have been a wall– and soaks her fingers on the dampness coming out of the cement. Then she takes her fingers towards Selma’s mouth and feels how she licks them weakly. She repeats the action once again, and on the third time, when she’s about to put her fingers on her own mouth, she feels the earth jumping again. Selma yells with dread and Rosario holds her very tight, because she doesn’t want to die alone.

Then there is peace again.

She feels the dust floating around herself because the air is thicker and hard to breath, but she’s still alive, and the world is quiet.

–Are you OK?

–Yes –answers Selma. Rosario tries to lay down closer to her and realizes that she can’t move her leg, that she can’t feel her leg. She starts to go through it with her hand and feels it swollen and hot, especially around the knee.

She’s scared.

Her hand returns to its original position on Selma’s belly, and when she touches her dress she feels the thick layer of dust settling down again.

Selma moans, and Rosario has the urgency of feeling her mouth with her fingers in order to confirm that she’s still breathing. Her hand starts its journey through Selma’s belly, her chest, her neck, and when it arrives to her face, it discovers a line of dampness. Instinctively, Rosario takes her fingers to her mouth. There, blended with the taste of dust, she recognizes the salty flavor of tears, and realizes that Selma has been crying in silence. She thinks about how despite of not drinking water for what it seems an eternity, Selma still has enough water in her body to cry.

***

One night, a horrible noise woke Rosario. Taken by her curiosity, she looked out of the window to figure out where it was coming from.

–It’s my nephew –declared don Chente, awake on his bed, for he never slept well because of the stomach burns.

–That’s an uproar! Sounds frightening.

–I told you it’s just my nephew. Now, go back to sleep!

His name was Enoc, and Rosario learned from his husband that he had some kind of an accident and that’s why he suffered great headaches at night. Rosario had watched him building a shack over the last week about a hundred meters down the hill from her house. And, listening to his desperate, painful yelling, Rosario remembered the poor, young woman that arrived the day before. She thought “Poor girl, having to put up with those shouts every night!”

Enoc had survived the bottle of ant’s poison he drank for love, and a few weeks later after he was released from the public hospital he married Selma. With the consent of don Chente, he built a shack on the same hill where Rosario and his husband had been living for a few years.

The shrieks continued waking up Rosario on the following nights, and for a few days she held back on her curiosity, because she truly wanted to talk to her new neighbor and ask her what had happened to her husband –since don Chente never cared to talk about it with her.

But her neighbor would never go out of the shack, and Rosario spent day and night in front of the window, waiting.

It happened on the morning of the third day. Don Chente had gone out to work on his plots and Rosario was feeding the hens as she saw the new neighbor coming out of her house with a wooden crate full of clothes. Hurriedly, she dropped the rest of the sorghum, went into the house, took the tallow soap and the first clothes she could find, and went running down the hill with the wooden crate balancing on her head until she catched up with Selma’s slender figure walking down the dirt path towards the river.

–Are you going to the river?

–Yes –answered Selma.

–To wash clothes?

Selma stopped and looked at her questioningly, and Rosario realized that she was asking absurd questions. She muttered “just like me”, and Selma continued down the path. She followed.

–My name is Rosario –said a few minutes later, after the embarrassment had faded away–. I live up the hill from you, I’m don Chente’s woman.

–My name is Selma.

With time, they became, despite their difference of age, good friends. But first Rosario found out that Selma was totally guileless in all practical things in life, so she made it her task to teach her how to ignore her husband when he’d come home drunk at night, not to wash her hair on new moon in order to avoid having gray hair early, or which lies were the best to deny herself to her man without hurting his pride. They ended up doing everything together: boiling beans, washing clothes in the river, taking the corn to the mill, having lunch when their husbands were away, brushing their long hair and sharing every detail of their lives during the long hours of wives without children.

***

Rosario takes back her hand from the damp wall. She introduces her fingers into her mouth, enjoys the humidity, and keeps silent.

–I don’t want to die alone –says Selma, and Rosario feels that she just read her mind. But she doesn’t answer at once. She lets Selma’s voice disappear on the darkness.

–Me neither –she mutters, without taking out the wet fingers from her mouth.

Then she hears a distant noise, and thinks: “Those are men’s voices, screaming. They’re moving rocks, they’re hitting things with metallic tools up there.

–Hold on, they’re getting us out. You have to be strong, Selma!

Selma does not answer, and for a second, Rosario is invaded by fear:

–Selma! Are you listening to me, Selma?

–I’m here –she says.

“Her voice tells me that she’s alive”, thinks Rosario, “but I can’t see her”. She realizes that in darkness everything is blended: The thoughts, the voice, the pain, the noises and the fear.

Rosario remembers her leg, which she doesn’t feel, which feels cold, which doesn’t know how to feel. She begins to touch her whole body once again, feeling about with her hand the skin covered by cloth and dust, making sure everything is still there.

She runs her fingers through her apron and feels a compact and multitudinous sound, and her hand, prey of the same anxiety attack that spreads about her heart, reaches the matchbox that she put away on her apron’s pocket before the earthquake. She manages to take it out of the pocket, manages to crawl into a position where she can use both hands, and manages to hold the matchbox with trembling hands, for she cannot see it. Her fingers open the box, take a match out to explore it, finding the bulky end where light, heat and life is produced. She feels the narrow sides of the box and runs the match against one of them.

Then the world inflames, and the light is so bright that for a few seconds she cannot see. But then her pupils get used to the brightness, and she sees many iron spokes standing out over her head, among a big mess of concrete and rock. She looks at her leg, which she doesn’t feel, and it looks black under the layer of dust that covers her whole universe. She looks at Selma’s little body next to hers, going over her with the light emanating from her fingers, and when she reaches her face she recognize the black lines of tears cutting her cheeks, and a black blood stain marking her temple and her hair. And before the match extinguishes burning Rosario’s fingertips and producing such a piercing burn on her throat that makes her understand that she couldn’t light another match, Rosario smiles, for she knows that she isn’t alone.

***

Suddenly, things started to fall apart. Don Chente employed Enoc in his plots, and then he gave him a mare. Then they started to come back from the plots late and drunk. Rosario had learnt that when men come back somber and stinking of guaro, things could end up badly. And one night when her husband came back late, silent and drunk, she heard shouts from Selma’s house. Only that this time they were woman’s shouts.

She began to put a blanket on her shoulders and looking for the sandals next to her bed when she heard her man’s voice.

–You stay here, that’s their thing.

Next day, when don Chente and Enoc were gone, Rosario ran down to Selma’s shack, and found her on her bed, her arms full with bruises and her face swollen. She cried, and crying hurt because her eyes were surrounded by coagulated blood.

Rosario sat next to Selma, feeling softly her bruised arms. Then she laid next to her without saying anything. Then she embraced her, and when she felt her very, very close, she felt her smell of sweat and tallow soap.

–I’m jinxed.

–Don’t say that, Selma.

–I’m jinxed and God doesn’t love me.

–Don’t say those things, Selma.

–It’s true. God doesn’t love me because years ago I killed the baby that I was carrying inside. And now He won’t give me another one.

–That’s not true, Selma. That’s not true.

–And how is Enoc going to love me if I can’t give him a baby?

Rosario felt with her fingertips the swollen outline of Selma’s face, and then, instinctively, brought her fingers close to her nose and inhaled.

A sudden, cold current traversed her from head to toes. She knew then, with clarity and dread, that she felt for Selma something she had never felt before in her life.

***

–Can I hug you?

Selma doesn’t answer, and Rosario begins to settle down next to her small, warm body. “She smells like bleach”, thinks Rosario, and remembers that that morning she sent her to wash the bed sheets of the bosses’ bedroom, since they were to come back from Miami tomorrow.

She covers Selma with her arm, with great gentleness, afraid to hurt her with the weight of her body. Selma says “thank you” with a dry voice:

–Thank you for being here with me.

Rosario rests on her elbow, ignoring the pain caused by the burns, ignoring that she hasn’t felt her leg for a long time now, ignoring that she can’t see anything, that she’s dying of thirst and that the lack of food makes her feel constantly dizzy and exhausted; ignoring that the world is full of earthquakes and wars and floods and brutal men. With great difficulty, Rosario rests on her burnt elbow, lays down next to Selma, and kisses her neck.

Her skin, as everything else in her world, tastes like dust. But that doesn’t stop her. She rests her weight even more on her burned elbow and gets closer to Selma, kissing her cheeks where she remembers seeing a dark line of tears that tastes like dust and salt. And then, without thinking too much, resting even more on her burns, she seeks Selma’s dry lips. She feels them tight against hers, and Selma says nothing. And to make sure that this is not a dream or something she imagined wrapped up in darkness, Rosario wets her lips with her tongue, and kisses Selma once again.

***

First, Rosario was terrified. She spent two days dizzy and vomiting, and even thought that she was finally pregnant. But she wasn’t. She felt terror. She felt uncertainty. Desperation.

A few days later, Selma had recovered enough from her bruises in order to walk up hill, so she went looking for Rosario at mid-morning, wondering why she’d left her alone for so long.

Rosario saw her showing up at the front door and all the scaffolding she had managed to build around her heart in order to convince herself that she felt nothing for Selma fell apart. She wasn’t even able to look at her on the eyes, because she was afraid to break into tears.

From that moment on, Selma sensed that something had changed between them, and they began to take distance.

Selma resigned to her boredom at home, without understanding what had happened, bearing the beastly mood and nocturnal blows from her husband, while Rosario spent whole days trying not to think of Selma when she washed her hair, when she looked at her body on the mirror, when she’d lay next to her husband at night, when she’d dream or grind corn. When she’d breath.

It took her a few weeks until the waters of her inner river settled. And, once at ease, Rosario could see her heart broken in two: on one hand she desired Selma like nothing else in the whole world. On the other hand she felt with dread, with alarm, that she was a monster.

Rosario decided then to suppress her desire little by little, gathering strength where she felt none, bearing the desolation caused by Selma’s or her husband’s nocturnal screams, convincing herself that her heart felt a little bit stronger every day. But at the end she just felt unbearably alone.

***

–I don’t want to die alone –thinks or says Rosario. She isn’t sure of what she says or thinks anymore. Then she listens to Selma whispering a few words, and she gets closer to her face in order to understand her:

–You’re the only one who ever loved me, Rosario. Now that I’m dying it feels nice to know that I was loved.

–Don’t say that, Selma…

But Rosario can say no more. She couldn’t tell her that she wasn’t going to die, that yes, she did love her, that she was the only person she had loved in her life. She couldn’t tell her any of that because the world began to knock over once again, to hit, to roar and to yell with all the might of its entrails.

Rosario holds Selma with all her strength, and feels solid pieces falling upon them. They are anonymous and stabbing. Afterwards, she feels the cloud of dust raising from underneath, invading everything, her nose, her throat, her chest, her leg that she doesn’t feel, Selma’s small and tranquil body, and every single particle of herself.

***

When the storm inside of her went away, Rosario started to think that it would be fair to poison Enoc. Is not that she could bear no longer the screaming at night. She’d do it because she felt that she owed Selma that much.

But her plans never took place, because one day don Chente fell off his mare totally drunk. And since he had been drinking with Enoc and it was known that they both had an aggressive temper after drinking and that in more than one occasion they had drawn out their machetes to one another, people started talking. They said that Enoc had kicked don Chente off his mare.

So one morning, Enoc left and never came back, leaving house and wife on their own. And for the first time in her life, Selma took the initiative on something, and she visited her old boss to ask her if she had a job for her and for another friend whom she trusted.

–You’re lucky –said her old boss–, because a friend of mine just inherited his parent’s house at Los Planes de Renderos. It’s a huge house, with three stories and classy. They don’t build them like that anymore. I think I might be able to get you both a job there.

***

Rosario wants to open her eyes by instinct, because if she opens them she’ll know that she’s still alive. But she’s afraid because she senses that something has changed. There’s a brightness outside of her eyelids, and she’s afraid of what that brightness might be.

She hesitates. Asks herself if she’s still truly alive. Finally, she gathers the necessary strength to open her eyes.

A light beam coming down perpendicularly from upwards burns her eyes. She tries to move but her body feels trapped among hard objects. She manages to free her hand from the rocks covering it, and moves it closer to the light, feeling its warmth on her skin. She feels that warmth entering her whole body, and she knows it insipid and odorless, and feels happy.

–Rosario, Selma! –she hears voices from up there.

The voices feel each time stronger, and Rosario screams or thinks with all her might: “We are down here, Selma and I”.

–They’ll pull us out –she tells Selma–. Soon they’ll be down here.

But Selma doesn’t answer. So Rosario moves her fingertips towards Selma’s face, although using her hands isn’t any longer necessary, because the light coming from up there illuminates everything. She looks at Selma’s tranquil face, the black lines of tears cutting through the gray layer of dust. Her eyes are open and fixed on something far away, and Rosario puts her fingertips on top of Selma’s mouth, yearning to find the soft and warm breeze of her breath.

BIO

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetuer adipiscing elit. Vestibulum bibendum, ligula ut feugiat rutrum, mauris libero ultricies nulla, at hendrerit lectus dui bibendum metus. Phasellus quis nulla nec mauris sollicitudin ornare. Vivamus faucibus. Class aptent taciti sociosqu ad litora torquent per conubia nostra, per inceptos hymenaeos.