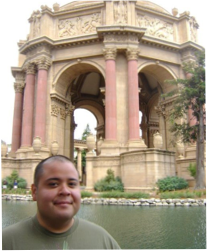

C. Adán Cabrera is the queer son of Salvadoran refugees. Among other publication credits, Carlos’s writing has appeared in Westwind, Switchback, From Macho to Mariposa: New Gay Latino Fiction, and Missing Pages: A Short Story Anthology. While living in San Francisco, Carlos was also a member of the 2010 Intergenerational Writers’ Lab and wrote for the bilingual newspaper El Tecolote. A 2011 Lambda Literary Fellow, Carlos is also a regular contributor to the online magazine Being Latino. Carlos holds an MFA from the University of San Francisco and a bachelor’s degree in English from UCLA. He currently divides his time between Los Angeles and Barcelona and is hard at work editing his first book, Tortillas y Sal, a bilingual collection of short stories about the many faces of the Salvadoran diaspora. Please visit his website at www.cadancabrera.com