BIO

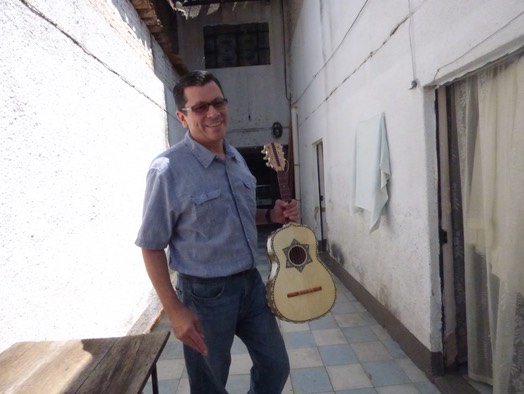

Arturo Urrutia is a student in the MFA creative writing program at the University of California Riverside-Palm Desert. He received a B.S. degree in biology from Cornell University in 1989. A native of the San Diego-Tijuana region, his literary focus is on the mixture of real, imaginary and fluid cultural elements that don’t always combine in harmony. He lives in San Diego with his wife and two children.

A Lucky Man

“Pete’s a lucky man,” Dad said over the phone.

“Dad, Pete’s wife is having an affair with her boss. She’s moving out to be with him; she doesn’t love Pete anymore,” I said louder, because my dad was a little deaf.

“She said she doesn’t love him anymore and she’s sleeping with another guy!” Dad shouted as if I was the one going deaf. “They don’t have children to fight over? Look, he’s never going to have an easier choice in his life. He’s a lucky man!”

I guess if you’re the kind of guy who has doubts about making a decision, Dad was right; Pete was a lucky guy. There wasn’t a thing he could do to rescue his marriage if Elsie wasn’t going to change her mind. The only thing left for him to do was move on.

But Pete couldn’t let Elsie go. He spent the hours at work staring at his computer monitor, frozen in a trance, so that anyone could see that something was wrong.

I avoided walking into the office I shared with Pete; I drove on all the levels of the parking structure, watching the red digits on the speedometer flicker from 3 miles per hour to 4, then back to 3. I delayed in the lunch room by toasting a bagel thirty seconds on one side, flipping it over for another thirty seconds, then repeating this two more times until it was completely burned and inedible.

“Good morning, Pete,” I said.

“Hey, John,” he muttered without taking his stare away from the monitor. Our desks faced each other and in the mornings, I could see the reflection of his monitor in the window behind him. For the last two weeks the monitor panel was a sky-blue that indicated a dead hard-drive or a disconnected monitor. I stared at his face, but he didn’t react.

“It’s Juan, dude,” I said, emphasizing the raspy “H” sound, but that didn’t get the laugh it used to. Pete was from Maryville, Tennessee; “born and raised”. He had never practiced Spanish outside of a classroom. His way of pronouncing my name sounded closer to John than Juan, or something that sounded like a French word.

About six months ago he asked me, “Say, John, how often do you and Maria have sex?”

If that question had come from someone other than Pete, someone I had no regard for, I might have said, “None of your fucken’ business.” But this was Pete, the young, Southern boy who called his dad “Sir” and his mother “Ma’am”. And I liked him.

“At your age, we were doing it about two or three times-a-week, four if things were really good,” I said. I was forty-five, almost twenty years older than Pete. I couldn’t really remember how often Maria and I had sex when I was that young; it was a guess.

“Always?”

“It might vary a little, but never on Sunday mornings. Maria says there’s going to be sex on our bed every Sunday at 10 AM, like church, whether I’m there or not. So, I’m always there.”

“What if it’s been longer?” he said.

“How long?” I said.

Pete tightened his Velcro watchband. Unlike me, he was incapable of telling a lie. When I’ve seen him confronted with an inappropriate question, such as, “Are you a democrat or a republican?” or “How many children do you plan to have?” Pete would simply smile, hold the gaze of the person and not answer the question because he had too much “good upbringing” to be rude.

“Three months.” he said. He added, “Don’t you think if you’re happy, it doesn’t matter how often you do it?”

“Not normal,” I said.

When Elsie came clean about the affair Pete went out to his backyard, pulled out of the ground the orange and avocado trees they planted two years ago when they first moved in together, thrashed them about until leaves and splinters lay scattered all over the yard, and then went back inside and pleaded with her to save their marriage. They could get counseling. They could take time off from work to be together. They could even move to a different city and start over. Elsie refused, however. She wanted a divorce so that her boss would get a divorce from his wife and they could move in together.

Pete and Elsie didn’t have kids, so there wasn’t that particular pretext for staying together, or that complication to stop them from splitting up. On the other hand, her boss was married and had three kids, the third born just months before Pete had discovered the affair. Elsie said that her boss had lots of reasons not to tell his wife right now. So, Pete and Elsie were still sleeping under the same roof, separated by a wall.

I had exhausted all my arguments to pull him out of this dark pit he was in. I thought of calling Jack, my best friend since childhood and lawyer, who could probably tell Pete what to do from a legal perspective. Pete rejected all my offers.

“It’s not your fault she cheated, Pete. You just got unlucky. You’ll find a better match,” I said.

Without any warning, he said, “Call your dad, ask him.” So, we did. And when dad told him he was a lucky man, we didn’t say anything more.

The phone call to Dad happened on a Thursday morning. Pete and I were both out of the office for the rest of the day, so I didn’t see him. On Friday, I parked in the first empty stall and skipped the bagel; I was anxious to see Pete, but he didn’t show up to work.

My marriage is as good as a marriage can be, but I can’t say that there won’t ever be a circumstance where I won’t wreck it all. I’m sure Maria loves me, but we don’t love each other all the time. I’ve fantasized about running off with a young woman. More than once. What man in his forties hasn’t? I’m careful not to fantasize to the point where I have the young woman look at the ridiculous thing my naked body has become, I still have shame.

I’m not the jealous type. I notice that Maria is more willing to make love the nights we watch one of her steamy soaps and she sees her man. After twenty years of watching television together, I know her type. When we go to a restaurant and I see a young waiter that’s her type, I’ll ask to be seated at his table. Shame doesn’t always stop me.

We were busy all week getting our son ready to return to the university, so Maria and I had not been intimate since the previous Sunday.

“This is your window,” said Maria Friday night. That’s her way of saying that she’s willing to have sex. It’s not seductive, but after twenty years of marriage you become careful about regulating the enthusiasm. You want to pace yourself, don’t over-commit.

“You don’t want to save it for Sunday?” I said.

“No, there’s not going to be a Sunday. We have the party tomorrow, the breakfast with your mother on Sunday and all the other things in-between. So, we’re not going to be on a normal schedule. Henry and Julie are at the movies. This might be your only chance.”

So we showered, jumped into bed, and showered again afterward. We were standing before the mirror, she in her bath robe and I naked, when Henry walked in. She was removing the hair that grew out of my ear and I was plucking the little black hairs sprouting on her neck. I call it our post-fuck pluck.

He looked at us with disgust and we looked back at him with amusement. We all returned to our activities; us to pluck and him to look for toothpaste under the sink.

“I hope I never look like that,” he said.

“I looked just like you; even better on the arms,” I said.

“He did,” said Maria.

“Grandpa has a saying about that, Henry; “I once saw myself the way you do now, and some day you’ll see yourself the way you see me now.”

Henry found the toothpaste and ran out holding his hands to his ears and said, “No, shut up!”

“Knock, next time!” I shouted after him.

I was up Saturday morning to see Henry off, back to school. He and I checked the oil and the other fluids in his truck.

“Dad, can I get an extra bill?” he said.

“You want me to bill you?”

“No, can you give me an extra hundred?”

“What for?”

“Just in case.”

“In case of what?” I said.

“Never mind,” he said. “Mom didn’t want to give me any more money.”

I handed him a hundred dollars, in twenties, before saying good bye.

“Go say bye to Mom and Julie,” I said.

“I did, already,” said Henry.

When Henry started the engine, Julie ran out barefooted in her pajamas. They hugged. I still get the lump in my throat whenever Henry leaves for school, but I also can’t wait until Julie goes, too. I feel that I’m racing against the clock and the sooner they are both graduated, moved out and living their own life, I’ll feel less pressure about my responsibilities to provide.

After Henry drove away I pulled my phone from my pocket and checked off the first line ‘Check Truck Oil’. The next line on the list was ‘Mow Lawn’, followed by ‘Wash Cars’, ‘Sweep Back Yard’, ‘Clean Barbecue’, and ‘Buy Charcoal’.

I promised Maria that I would take care of everything outside the house if she took care of things inside the house. It was a work party for her employees, so she was grateful that I was helping.

Jack was supposed to show up at noon to help me barbecue. The party would also start at noon. Maria thought that if I was outside, my interactions with her co-workers could be minimal.

On principal, I disagreed with Maria about having a work party at our house; I believe there should be a clear separation between work-life and personal-life. Maria mixes both sides of her life. I often think she gives priority to her work over her home. It was a farewell party for her co-worker moving to Texas. He was going to manage a mortgage lending group for the bank.

Maria’s bank was extremely competitive. Every year she got rid of the latest guy who had tried to replace her. If the fight was dirty, she would send the loser to an ugly town, in a dead end position. This party was for Walter, one of her favorites. I didn’t like the guy because he was a kiss-ass on the surface, but I could tell that he was your typical backstabbing, money-grubbing banker who tried to steal Maria’s job. He lost, just as all the other guys who had gone up against her in the last ten years. What I most disliked about Walter was how much Maria liked him. She talked about him all the time. Walter did this. Walter did that. Walter was all she talked about.

Walter was fifteen years younger than Maria and had the hot-shot degree from Stanford, so he felt entitled to Maria’s job. Maria is no fool; she set him up, promoted him and then shipped him to the outskirts of Dallas. Now, she graciously invited her co-workers to our home to wish Walter and his wife, luck at his new post.

She was trying on dresses for the party, walking in and out of the closet to look at herself in the full-size mirror. “You should’ve rented a bowling lane or a party room at a bar to celebrate his departure,” I said.

“Stop whining. You know the drill; just smile and don’t share any information. Got it, baby?”

“Did you learn that in your management books?”

She stepped back from the mirror and raised her perfect eyebrows at me, “You know, I don’t recall the chapter on protecting your husband from regretful behavior.” She looked back at herself in the mirror and made some adjustments to the dress around her thighs. “What do you think of this dress?”

Maria was drop-dead gorgeous when she was young. She was still gorgeous, but you can’t expect a forty-three year old person to look like she was twenty, especially after a twenty year career sitting behind the desks at banks, working long hours, and two pregnancies. She filled the gauzy, pleated top of the summery, white dress generously, but the skirt hugged her bottom in an unattractive way.

“I think you’d look better in another dress,” I said.

“Why?” she said.

“The dress has a funky shape. It’s nice up top, but the fabric doesn’t go well below the waist.”

She pulled at the hem, readjusted the waist. “I bought it for this party.”

“You have much nicer dresses than that,” I said.

When she went back into the closet to find another dress, I hurried out of the room.

Jack was invited because he is the expert on running the grill at our house. I like him around because he’s a lawyer and scares the crap out of people. I think Maria likes him around because he can filter his conversation to the setting. He arrived as soon as I set down a bag of prime mesquite charcoal and a tin can of lighter fluid next to the barbecue. I waved my hand before the barbecue and bowed in reverence. He scowled at me and kicked the tin can so hard that it popped open when it hit the wall of the backyard. I ran to stop the spill of lighter fluid.

“What is that?” he shouted pointing to the can.

“What the hell do you think?” I said.

“This is all poison and crap,” he said, pointing to the bag of charcoal.

Jack brandished a hatchet; I don’t know where he got it and why I had not seen it. He walked to a pile of firewood, that I used in the chimney, and started splitting wood with the hatchet.

“What was that?” said Maria sticking her head out the door.

“Nothing,” I said pushing her back inside.

“Is the meat ready?” Maria said.

“Almost,” I said.

“Didn’t we agree that it would be ready by noon?”

“The people aren’t even here,” I said.

The doorbell rang and Maria wiped her hands on a towel she was holding. She looked at me with contempt, just like Jack had done.

“Cook the chicken first, in case the children are hungry,” said Maria.

Outside, Jack was making a bed of dry bramble in the barbecue.

“Maria wants the chicken first,” I told Jack.

“The eggplant will be first, followed by the onions, tomatoes and peppers. After the vegetables I will cook the meats,” he said.

I went back inside to see Walter coming through the hallway into the kitchen.

“Juan, how are you?” said Walter.

I could hear Maria in the other room, cooing to what must have been Walter’s child. I heard Walter’s wife speaking with a strong foreign accent, trying to say something which I could not decipher. I couldn’t remember if she was Romanian or Croatian. I don’t know, but I remembered that she was gorgeous.

When they came through to the kitchen, Maria was leading a child by the hand toward the table where she had some cups with lids and straws. Walter’s wife came in right behind her in the same dress that I had told Maria not to wear. It wasn’t a horrible dress on her. She filled the top perfectly, not overly stretching the pleats as Maria had done, but gently weighing down the subtle seams. The bottom was even more stunning because she was a twenty-year old woman.

“Hello, I am Monica,” Walter’s wife said, reaching out with her hand.

I was polite. I greeted her and made the casual praise of her son.

“I need to get back out to the grill,” I said. Maria followed me to the door.

“What do you think of her dress?” Maria said privately.

“Aren’t you glad you aren’t wearing the same dress?” I said.

“Are you?” said Maria. There wasn’t love in her voice.

“We were supposed to have the meat ready before the people got here,” I told Jack.

“No, the meat should be served to the people when they are seated at the table and not the other way around; they should hear the juices sizzle when you set it on the table.”

You might say that Jack is a purist. He learned this from the people of the Artsakh region of Armenia, where he spent half of every year teaching human rights to law students. According to Jack, the people of Artsakh are resilient people. They chop their own wood and butcher their own animals to eat. In no time he had a fire going and was charring eggplants, onions, tomatoes and peppers.

I peeled the charred skins off the vegetables, dipping my hands in a bowl of warm salt water; I don’t know why Jack insists I use warm salt water, my instinct is to use ice water, (again, that’s how they do it in Artsakh) and placed the vegetables on white serving plates.

Jack placed metal skewers with chunks of chicken, beef and mutton on the fire while I carried the vegetable plate into the house.

The house was full now. There were people seated all over the dining room and living room and standing everywhere else, being very social. Children ran about.

“Go wipe your forehead,” said Maria.

“I’m not done outside,” I said.

I got the stern brows again, so I went to the bathroom to wash up.

Maria was right; I had lots of grease and ash from the barbecue on my glasses and face. My plan had been to jump into the shower after I was done cooking, but it wasn’t a bad idea to clean up a little.

When I walked out of the bathroom Monica was walking in. Again, she took my breath away. I guess she noticed my reaction because she immediately turned away, rushed into the bathroom and locked the door.

“Don’t embarrass me,” was what Maria always warned before social events, especially if she wasn’t going to be with me. She meant that I shouldn’t make a fool of myself.

As I came into the dining room Jack was holding the skewers of sizzling meats over the white porcelain plates and peeling them off to the ‘oohs’ and ‘ahs’ of the guests. Equally impressive was that he had changed out of his t-shirt and was now wearing a loose white button shirt with colorful embroidery on the collar and buttonholes. He was also wearing a small, cylindrical hat with some gold colored embroidery. He looked clean. Although he had been the person dealing with the smoky barbecue, he was clean.

I didn’t shower. As soon as I placed a juicy chunk of lamb in my mouth, I couldn’t stop eating until I had tasted everything that Jack had cooked.

Jack rinsed the demitasse coffee cups that he brought back from Armenia. They were too small, so I never used them unless it was to play tea time with Julie when she was younger. He arranged them in a circle and poured the bubbling coffee that erupted from the volcano shaped copper kettle and landed perfectly in each cup. I took long slurps of the hot liquid until the coffee grounds caught on my teeth and I chewed on the grounds.

“Everyone watch me and do exactly as I do,” Jack said.

He placed the inverted saucer on top of the cup, like a lid. We imitated him. He rotated the cup inward until it was upside down and placed it on the table before him.

“Now, turn clockwise three times,” he said.

Maria and I knew that Jack was about to read the patterns of coffee grounds left on the cups and tell us what was in our futures. This is something that Jack and I always did for each other when we had our coffee, but it was something that he rarely did with anyone else.

Monica’s child was palming her thigh for attention, so I couldn’t blame her for turning the cup counter-clockwise and invalidating the magic. I didn’t say anything. Jack raised an eyebrow, he had noticed. He also said nothing.

I’m not a superstitious person, but I don’t mock those who are. Especially if a good time results from it.

I won’t say that Jack has supernatural abilities, but he knows how to read a person; the nervous tick of an eye, the furrowed forehead of someone who stayed up late worrying about money, the high pitched voice of a person who is unaccustomed to speaking up. I don’t know how he does it. Whatever way Jack has of reading people, it’s practically infallible. He reminded the spinster about her school-teacher grandmother who came to America during an Irish famine. He told the receptionist about her philandering second husband, the cancer that took her first husband and the happiness she would find with her third husband, with whom she will finally have her “happily ever after”, to the collective sighs from us.

I waited for Monica’s fortune. Her son was still playing with her dress, sliding it with both his hands up her thigh, while blowing raspberries, and when it was at a level which she thought was indecent, she slid it back. That didn’t deter the little angel, because it was a game now. Again, he pushed it up her thigh.

I wanted Jack to tell her about the difficult road ahead in Dallas. I wanted him to say something bad about Walter.

Jack took off his glasses and tilted his head from side to side, a good sign of bad news, before saying, “You have a lot of changes in your life,” now pointing into the cup and tilting it so that she might see the proof herself. Meanwhile, her son slid the dress past her knee, up to the fine, whiter skin of her thigh.

“I know, I have a baby now,” she said.

“No!” Jack said and slapped the table. “This is the future; your cup is the future.”

Excellent, Jack. Tell her how Walter is a loser. How she runs off with a better man; me.

“More change is coming,” said Jack. “You are small, but all these hills around you must be overcome.”

Her dress was past the midline of her thigh and I could see the soft, fleshy muscles.

“There is a girl waiting for you,” said Jack.

“Yes! We want a sister for Freddy,” she said.

No, goddamn it Jack. Wrong way!

“Stop!” she said, and both Freddy and I were stunned. She pulled her dress down, and I looked away, to my cup, hoping that Maria had not seen me staring at Monica.

After the party, Karla, the cleaning lady Maria hired one day a week and on special occasions, was cleaning the kitchen while Jack, Maria and I sat in the living room sipping brandy.

“Jack, you were a hit tonight. We all loved you. You made it so much fun,” Maria said.

“Thank you. Yes, I agree, we had a good crowd tonight,” Jack said.

“Would anyone like to thank me, too?” I said.

“To Juan,” said Maria, raising her glass.

“To Juan,” said Jack, and we all knocked back our glasses.

After Jack left the house Maria and I continued drinking in the living room. The house was clean, so Karla left. We were alone.

“Where is Julie?” I asked.

“She’s spending the night at your mom’s house. It’s all the cousins’ sleepover at grandma’s house.”

“So, we’re alone tonight?”

“That’s what it looks like,” said Maria. “I’ll pick her up when we meet for breakfast tomorrow.”

“Who’s next on your list?”

“What are you talking about?”

“Who are you sending off to another office? Who’s next?”

“Don’t be such a cynic. Walter is not being sent off. He’s following an opportunity at a new office in a growing area. This is a huge opportunity for him. He earned this.”

I didn’t want to argue. So, I sat quietly staring at Maria.

“It’s called making your own opportunities instead of waiting for something to fall out of the sky.”

“Is that what I’m doing; just waiting for an opportunity to fall out of the sky?”

“Hasn’t it been eight years since your last promotion?”

“Ten. Are you counting?”

“Walter is successful and he’s at a higher level than I was at his age; he’s probably going to get further in this company than me. So, don’t criticize him.”

“He didn’t make a play for your position?”

“That’s the point in life, ‘to make a play for something better’. You’re either moving up or you move somewhere else, there is no third option.”

“You sound like you’ve bought into this whole idea of a competitive society. What if you don’t move up, no matter what you achieve?”

“It’s a high achieving culture. Nobody wants to hear the poor defeated sob story. You live in one of the most privileged areas on the planet, if you can’t thrive here; it’s pretty pathetic; especially if you criticize those who succeed.”

Maria had a point; although I tried to play the uninjured cool cat, my wounds festered daily when I was frustrated at work. I guess it’s just pride keeping me from admitting that I continuously attempt and fail, rather than saying I just don’t care at all.

“Do you think I’m a failure?”

“It’s hard to sympathize with you when you’re being mean to others. But no, I’m not saying you’re a failure. You just got to move on if you’re not happy.”

“Do you think I’m . . .?”

“What?”

I was about to say “insecure” before I realized how insecure that sounded.

I rushed to work Monday morning, anxious to see if Pete had resolved his situation. He wasn’t there. Nine o’clock came and passed; our usual “catch-up” hour, but he didn’t show up. I left the office for a few hours to go to meetings where I covered for him. When I returned to the office at noon, the red indicator light on my voicemail was flashing. I entered my password and listened to the message. The voice said; “Juan, Pete here. I wanted to let you know that I resigned this morning. I don’t have anything to keep me here so I don’t plan to go to work. See you around. Good luck.”

All of that happened two years ago. That was the last time I heard from Pete, or of Pete. I never bothered to look him up. I imagine that he found another place to work and hopefully a better relationship. Before the company hired someone to replace him, I moved into his desk, however. I still sit at his old desk and I think of him sometimes.

Walter became Maria’s little pin to prick my side whenever we argue about careers. If she wants to make me feel insufficient she says how Walter got promoted to a new office, a bigger city, a better job and of course how he and Monica keep those babies coming. It doesn’t bother me; not too much. I know exactly where I stand. I can’t just pick up and leave this life; Henry finished school, but Julie is about to start college next year and I’m going to have her tuition bills to pay.

Sometimes I think of Pete while I stare at his old computer monitor. I think of getting in my car; I think of driving on the highway until I find Pete and follow him somewhere else.

BIO

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetuer adipiscing elit. Vestibulum bibendum, ligula ut feugiat rutrum, mauris libero ultricies nulla, at hendrerit lectus dui bibendum metus. Phasellus quis nulla nec mauris sollicitudin ornare. Vivamus faucibus. Class aptent taciti sociosqu ad litora torquent per conubia nostra, per inceptos hymenaeos.